With AI warning, Nobel winner joins ranks of laureates who’ve cautioned about the risks of their own work

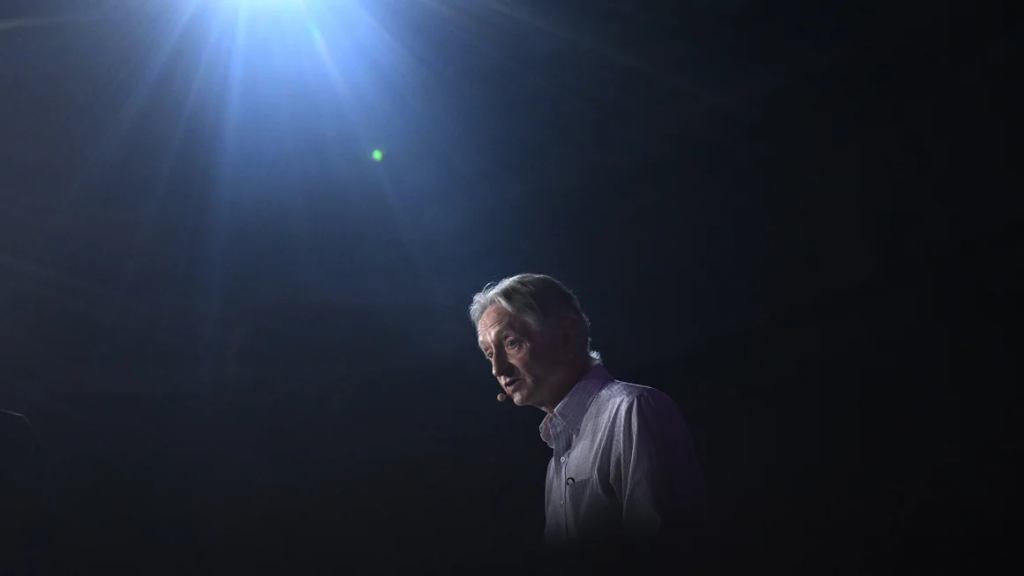

When computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton won the Nobel Prize in physics on Tuesday for his work on machine learning, he immediately issued a warning about the power of the technology that his research helped propel: artificial intelligence.

“It will be comparable with the Industrial Revolution,” he said just after the announcement. “But instead of exceeding people in physical strength, it’s going to exceed people in intellectual ability. We have no experience of what it’s like to have things smarter than us.”

Hinton, who famously quit Google to warn about the potential dangers of AI, has been called the godfather of the technology. Now affiliated with the University of Toronto, he shared the prize with Princeton University professor John Hopfield “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

And while Hinton acknowledges that AI could transform parts of society for the better – leading to a “huge improvement in productivity” in areas like health care, for example – he also emphasized the potential for “a number of possible bad consequences, particularly the threat of these things getting out of control.”

“I am worried that the overall consequence of this might be systems more intelligent than us that eventually take control,” he said.

Hinton isn’t the first Nobel laureate to warn about the risks of the technology that he helped pioneer. Here’s a look at others who issued similar cautions about their own work.

1935: Nuclear weapons

The 1935 Nobel Prize for chemistry was shared by a husband-and-wife team, Frederic Joliot and Irene Joliot-Curie (daughter of laureates Marie and Pierre Curie), for discovering the first artificially created radioactive atoms. It was work that would contribute to important advancements in medicine, including cancer treatment, but also to the creation of the atomic bomb.

In his Nobel lecture that year, Joliot concluded with a warning that future scientists would “be able to bring about transmutations of an explosive type, true chemical chain reactions.”

“If such transmutations do succeed in spreading in matter, the enormous liberation of usable energy can be imagined,” he said. “But, unfortunately, if the contagion spread to all the elements of our planet, the consequences of unloosing such a cataclysm can only be viewed with apprehension.”

Nonetheless, Joliot predicted, it would be “a process that [future] investigators will no doubt attempt to realize while taking, we hope, the necessary precautions.”

1945: Antibiotic resistance

Sir Alexander Fleming shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in medicine with Ernst Chain and Sir Edward Florey for the discovery of penicillin and its application in curing bacterial infections.

Fleming made the initial discovery in 1928, and by the time he gave his Nobel lecture in 1945, already he had an important warning for the world: “It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them, and the same thing has occasionally happened in the body,” he said.

“The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops,” he went on. “Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and, by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant.”

It was “such an important and prescient thought so many years ago,” said Dr. Jeffrey Gerber, an infectious diseases physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and medical director of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program.

Nearly a century after Fleming’s initial discovery, antimicrobial resistance – the resistance of pathogens like bacteria to drugs meant to treat them – is considered one of the biggest threats to global public health, according to the World Health Organization, responsible for 1.27 million deaths in 2019 alone.

The key part of Fleming’s warning may have been antibiotics’ excessively wide use rather than the idea of low dosing.

“More often, people are given antibiotics entirely unnecessarily,” Gerber told CNN in an email. And “more and more often, we see bugs that are resistant to almost every (and sometimes every) antibiotic we have.”