This growing fungal disease outbreak spreads through dust and dirt

SALINAS, CA − A lethal fungus has quietly spread in the soil across the West. Now, it’s threatening areas well beyond the dusty deserts and valleys where it likely originated.

Valley fever, a disease caused by the fungus Cocciodioides, was once concentrated in the American Southwest. In an era of increasingly extreme weather, the disease is thriving in areas once considered cool and temperate.

Ahead of the disease’s peak fall and winter seasons, health authorities are scrambling to raise awareness about its easily missed signs and symptoms before the spread worsens.

“I’m not sure we can prevent people from getting valley fever,” said Christie Michie, assistant director of public health in California’s Monterey County, a cool coastal agricultural region that once had just a couple of dozen cases a year but now averages hundreds. “It’s very difficult to avoid dust in our environment. But what we don’t want is people get really sick with valley fever.”

In 2024, nearly 12,500 cases were reported across California, a record high, according to state health data. Less than a quarter-century ago, the state reported just 1,000 cases.

The disease presents growing risks not just for agricultural workers accustomed to tilling soil but also for those who move to new suburban developments or spend the weekend on a golf trip in a region where the fungus is present.

How valley fever spreads

People exposed to the fungus may not get valley fever, which is also called Coccidioidomycosis. But those who contract the disease can develop symptoms of pneumonia lasting a few weeks or more that typically appear one to three weeks after breathing in fungal spores. Symptoms include:

- Rash

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Fever

- Headache

- Fatigue

Small numbers of people who get valley fever, 5% to 10%, will develop serious or long-term complications in their lungs, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, people with diabetes, and Black and Filipino people are at higher risk of severe illness.

In about 1% of those infected, the disease spreads to other parts of the body, such as the brain, bones and other organs.

A single valley fever infection usually results in lifelong immunity, but there is no vaccine against it. Antifungal medications can help prevent more severe outcomes, the CDC says, which is why it’s so crucial not to miss the diagnosis.

Heavy rainfall followed by drought creates spores that are infectious, said Dr. George Thompson, codirector of the Center for Valley Fever at the University of California, Davis. The fungus releases spores that rise into the air and can be inhaled, Thompson said. Even a single spore can cause the disease, he said.

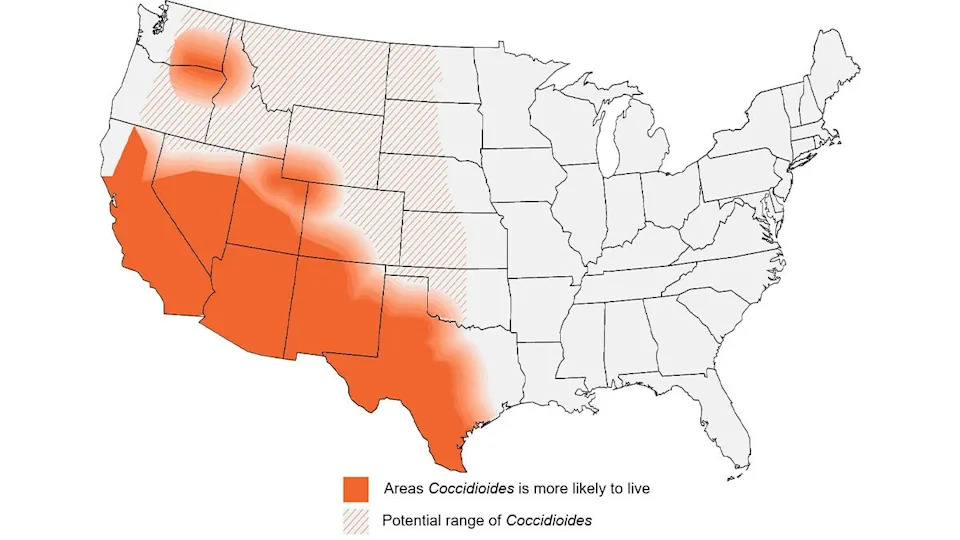

It already has spread well beyond California’s interior San Joaquin Valley, where the disease takes its name, and the Arizona deserts that have the nation’s highest numbers of cases.

Projections show valley fever has spread well beyond the Southwest because of prolonged drought and rising temperatures. The fungus already has been infecting people as far north as Washington state and Oregon, and by the end of the century, studies show the fungus is expected to flourish beyond the Canadian border and into the Midwest.

“There’s not a lot of awareness at all,” said registered nurse Dana Bruckner, 48, whose dog developed valley fever, probably from her backyard in Bakersfield, a San Joaquin Valley city that has the highest numbers of cases in California.

She and a colleague, Bianca Torres, lead monthly Zoom calls on behalf of Kern Medical Center’s Valley Fever Institute in Bakersfield.

Their goal is to teach patients and others about the disease, which can be mistaken for flu or bronchitis, said Torres, a program research coordinator whose father was hospitalized for the disease when she was a child. That way, people can talk to their doctors about the possibility of having valley fever.

“It can go undiagnosed,” with rounds of antibiotics not effective, Torres said. “It’s important to also advocate for yourself.”

In Steinbeck country, disease lurks in soil

Climate change has been particularly noticeable along California’s Central Coast, where fertile valleys have long been aided by cool breezes off the Pacific Ocean.

Row crops of strawberries and leafy greens line the Salinas Valley, where daily fog rolls in between two mountain ranges that John Steinbeck detailed in his quintessential American novels.

Today, it’s where valley fever has taken a foothold. Provisional California health data shows that Monterey County, where the Salinas Valley is located, experienced the largest increase in cases by county this year.

Michie, of the county health department, cautions that early state public health data ‒ at 348 cases so far this year ‒ show a higher case count than local data, at about 275 cases. Even so, she said, conservative estimates are on track to surpass the previous year’s record of 358 cases.

“We’ve gotten to the point where if you’ve got pneumonia … we’re thinking about it right up front,” said Dr. Allen Radner, an infectious disease specialist at Salinas Valley Health, who has been dubbed the area’s “cocci guru.”

Two decades ago, Radner saw one or two cases a month. Now, during the fall’s peak infection season, he regularly sees three or four cases a day.

New to valley fever

Typically, those most at risk are people exposed to soil when it’s disturbed ‒ farmworkers, construction workers and prison inmates incarcerated in arid, remote areas.

Bill Perske fits none of these categories. The 39-year-old butcher from San Luis Obispo County had never heard of the disease when he developed a lingering cough, fever and lung problems in late 2023. He recovered and went back to work, but a few months later, he started having migraines and vomiting.

Near the end of 2024, he went blind for about 10 minutes and had a seizure in an ambulance.

An MRI showed he had hydrocephalus, or a buildup of fluid in his brain. After a spinal tap, he was finally diagnosed with the disease, probably more than a year after he contracted it.

He still experiences fluid buildup in his brain and is set to have a port installed to help it drain.

Perske said more people should be aware of the disease before it’s too late.

“If not, you could just die, straight up,” he said. “You get written off as a statistic.”

Eduardo Cuevas is based in New York City. Reach him by email at emcuevas1@usatoday.com or on Signal at emcuevas.01.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Growing fungal disease outbreak spreads through dust and dirt